The Oslo Accords were a landmark moment in the pursuit of peace in the Middle East. Actually a set of two separate agreements signed by the government of Israel and the leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)—the militant organization established in 1964 to create a Palestinian state in the region—the Oslo Accords were ratified in Washington, D.C., in 1993 (Oslo I) and in Taba, Egypt, in 1995 (Oslo II). While provisions drafted during the talks remain in effect today, the relationship between the two sides continues to be marred by conflict.

Although the Oslo Accords were noteworthy in that the PLO agreed to formally recognize the state of Israel and that Israel, in turn, allowed the Palestinians some form of limited self-governance in Gaza and the West Bank (the so-called Occupied Territories), they were originally seen only as a stepping-stone toward the ratification of a formal peace treaty between the two sides that would end decades of conflict.

However, the Oslo Accords have yet to result in any lasting peace—and their overall impact remains up for debate.

The negotiations between Israel and the PLO that ultimately led to the Oslo Accords began, in secret, in Oslo, Norway, in 1993.

Neither side wanted to publicly acknowledge their presence at the talks for fear of generating controversy. Many Israelis considered the PLO a terrorist organization, and thus would have seen the talks as violating the country’s prohibition on negotiating with terrorists.

The PLO, meanwhile, from its inception had not formally recognized the legitimacy of Israel, and its supporters would have considered a formal acknowledgement of the Jewish state’s right to exist a non-starter.

Leaders from both sides sought to make inroads toward lasting peace, at the behest of the United States and other world powers, and they came to Norway hoping to build upon the Camp David Accords, which were signed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin in September, 1978.

The Camp David Accords established the so-called “Framework for Peace in the Middle East” and brought about the end of simmering conflict between Egypt and Israel.

They also called for the creation of a Palestinian State in the area known as Gaza and on the West Bank of the River Jordan. However, because the Palestinians were not represented at the talks, which were held at the country retreat of U.S. President Jimmy Carter, the resulting agreement was not formally recognized by the United Nations.

As the PLO and representatives of the Israeli government arrived in Norway some 15 years later, the Camp David Accords served as both a model and starting point for the latest negotiations, in that the ultimate goal was to build a framework for the creation of an independent Palestinian state.

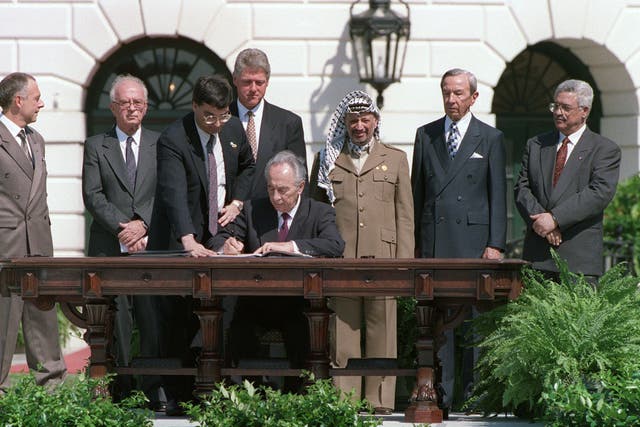

Seated at the table for these important talks were noteworthy leaders, including PLO head Yassir Arafat, former Israeli prime minister Shimon Peres, Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and Norwegian deputy foreign minister Jan Egeland. The Norwegians effectively served as mediators between the two sides.

However, before both sides could begin talks, there was the not-so-small matter of each recognizing the legitimacy of the other.

Indeed, just days prior to the formal signing of Oslo I, both sides signed a “Letter of Mutual Recognition” in which the PLO agreed to recognize the state of Israel (prior to this agreement, they had viewed the country as existing in violation of international law since its formation in 1948) and the Israelis acknowledged the PLO’s role as a “representative of the Palestinian people.”

In addition to the “Letter of Mutual Recognition,” Oslo I established the “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements,” which established the Palestinian Legislative Council (essentially, a freely elected parliament) and set the parameters for the gradual withdrawal of Israeli forces from Gaza over a five-year period.

Oslo I also set the agenda for the follow-up agreement that became known as Oslo II, which would include discussion of the future governance of the city of Jerusalem (both sides claim it as their respective capital) as well as issues concerning borders, security and the rights, if any, of Israeli settlers in the West Bank.

A protocol for free elections for Palestinian Authority leadership was also established.

Oslo II, which was signed two years later, gave the Palestinian Authority, which oversees Gaza and the West Bank, limited control over part of the region, while allowing Israel to annex much of the West Bank, and established parameters for economic and political cooperation between the two sides. As part of the treaty, for example, both sides were prohibited from inciting violence or conflict against the other.

Israel also collects taxes from Palestinians who work in Israel but live in the Occupied Territories, distributing the revenue to the Palestinian Authority. Israel also oversees the trade of goods and services into and out of Gaza and the West Bank.

Unfortunately, any momentum gained from the ratification of the Oslo Accords was short-lived.

In 1998, Palestinian officials accused Israel of not following through on the troop withdrawals from Gaza and Hebron called for in the Oslo Accords. And, after initially slowing down settlement construction in the West Bank, at the request of the United States, the building of new Israeli housing in the region began in earnest again in the early 2000s.

Conversely, critics of the Accords said that Palestinian violence against Israeli citizens increased in their aftermath, coinciding with the increasing power of the Palestinian Authority. These critics felt that the Palestinian Authority was failing to adequately police Gaza and the West Bank, and identify and prosecute suspected terrorists.

With these disagreements providing the backdrop, negotiators from both sides reconvened, once again at Camp David, with the hope of following up on the Oslo Accords with a comprehensive peace treaty.

However, with the United States playing a key role in the negotiations, the talks soon collapsed, complicated further by the impending changes in American leadership (the second term of President Bill Clinton would end, and he would be replaced by George W. Bush in January 2001).

In September 2000, Palestinian militants declared a “Second Intifada,” calling for increased violence against Israelis after Sharon, who as prime minister visited the Temple Mount—a site sacred to both Jews and Muslims.

The period of violence on both sides that ensued dashed any hopes of lasting peace, and the Israelis and Palestinians have not held substantive negotiations since.

Although some provisions of the Oslo Accords remain in effect—namely, the role of the Palestinian Authority in governance in Gaza and the West Bank—many of the provisions have long been abandoned.

The Oslo Accords. Office of the Historian. United States State Department.

Oslo Accords Fast Facts. CNN.com.

Shattered Dreams of Peace: The Road from Oslo. PBS.org.

The Oslo Accords. Global Policy Forum.